The survivals of Steven Hovagimian

by Christina Schweighofer

Steven Hovagimian’s life began with a bargain. When the boy emerged from his mother’s womb on a kitchen floor in Al Quamishli, Syria, he came out blue. He was a piece of meat, his grandmother said later. The boy’s mother, Angel, a woman with large dark eyes and black hair, had born three children before Steven, but only the oldest, Sarkis, had lived more than a year. The memory of those and many other losses in their bones, the women called a neighbor for help. He’s not going to make it, she said. Take him to the priest, have him baptized and bury him.

Steven’s grandmother, an Armenian Christian, knew better. On that January morning in 1963, she wrapped the newborn in a white sheet and ran off with him to the nearest church, Saint Kevork, a place where many prayers had been offered. The bundle in her arms, she knelt at the altar and ventured a deal: If you save this boy, God, I will not cut his hair for seven years, and I will make sure he always wears one earring.

Hovagimian indeed grew up as a girl until he was 7; pictures on Facebook show him with bows in his hair and an earring. (These days, he rarely leaves the house without a jacket and tie.) “People believed that there are white angels and black angels,” Hovagimian told me one day over lunch at Hatsatoun Restaurant in Glendale, a suburb of Los Angeles. “The white angels deliver the babies, and the black ones take them away. But if it was written that the black angel should go to the house of the Hovagimians and take the newborn son, the angel would go there, find a girl with an earring and leave the child untouched.” The belief came from pagan times.

Once the ominous seventh birthday had passed, Steven’s parents assumed their son safe. He became what he had been all along, a boy. Little did Angel and HagopHovagimian know then, that they would fear for their son’s safety again only four years later. Let alone could they anticipate which drastic measures they would employ to ensure his survival.

Steven Hovagimian’s biography, like that of many Armenians, is deeply intertwined with the tumultuous history of the Middle East and the bordering regions. Stalin’s expansionist politics, the wars between the Arabs and Israel, the Lebanese Civil War and the Islamic Revolution in Iran all came into play. But more than anything, one event has echoed down through the generations and into this man’s life: the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

The Armenians are one of the oldest surviving civilizations in the Middle East, with the earliest record of an Armenian kingdom dating back to the 6th century BC. At the time of Cicero, during the 1st century BC, the Armenian empire encompassed the area now covered by central and eastern Turkey, Lebanon, large parts of Iran, Syria and Israel. Its ruler, King Tigran II, was so mighty that Cicero purportedly remarked that he made the Republic of Rome “tremble before the prowess of his arms.” Since then much water has gone down the river Euphrates, and for long stretches of the past two millennia Armenians did not even have a state of their own but depended instead on the goodwill of the Russians, Persians and Turks.

Petros G. Malakyan, an assistant professor for Leadership Studies at Indiana Wesleyan University and an immigrant from Armenia himself, believes that centuries of dependence upon other nations have changed the psyche of his people. “A significant number of Armenians today believe that Armenia will not survive without foreign powers,” he wrote in a recent paper.

But Armenians have also learned to be wary of protectors. Speaking of modern day Armenia, Hovagimian once told me: “The Russians have [the country’s] economy in their hands. They bought everything. They said, here is the money and give me the electricity. Here is the money and give me the gas. I will control the gas. And, God forbid, one day when Russia says I have enough of you — they will freeze to death.”

God forbid, one day — Hovagimian’s fears are grounded in his people’s repeated experience of oppression and persecution, be it at the hands of the Persians in the early 17th century or at those of the Turks during the Armenian Genocide 300 years later.

The Armenian Genocide of 1915, the systematic attempt of the Ottoman Empire to extinguish the Armenians, began with the arrest and subsequent murder of several hundred Armenian intellectuals on April 24th, 1915. In the following months, the ruling Turks, who perceived the Armenians as a threat to their own newfound identity, passed laws to disarm, deport and expropriate all Armenians. Soldiers led death marches into the Syrian desert, raped women and girls, and shot entire families. Hundreds of thousands of Armenians succumbed to thirst, hunger and exhaustion.

In 1919, the American Ambassador in Constantinople, Henry Morgenthau, wrote about the events: “I am convinced that the whole history of the human race contains no such horrible episode as this. The great massacres and persecutions of the past seem almost insignificant when compared with the sufferings of the Armenian race in 1915.” Yet, no one intervened. By the time the first genocide of the 20th century ended in 1922, about 1.5 million Armenians had died.

The successor states of the Ottoman Empire, including present-day Turkey, have always disputed that the planned extermination of the Armenian people ever happened. This denial keeps the Armenians’ wounds festering — but it is also part of the glue that unites the Armenian diaspora across all borders. Year after year, on April 24, Armenians all over the world gather for demonstrations and protest marches, demanding that countries like the United States officially recognize the genocide and then put pressure on Ankara to do the same. (Washington has been reluctant to do so, because it doesn’t want to alienate Turkey, a strategically important Nato partner.)

Steven Hovagimian and I first met at one such march, three years ago in the Little Armenia neighborhood of Los Angeles. An immigrant from Austria, a country that carries tremendous historical guilt of its own from the Holocaust, I was there as a reporter. Hovagimian walked with the local Armenian dignitaries leading the crowd of about 5,000 people. The event had almost ended when he approached me. “I saw you take pictures and notes,” he said. “Are you a writer?” I introduced myself. Upon hearing my last name, which is as Austrian as a name can get, the man with the tie in the colors of the Armenian flag, red, blue and orange, beamed at me. “Ich bin ein Österreicher,” he said. “I am Steven. But in Austria I was Stefan.”

An Armenian from Austria? My eyes widened as I stared at the man in front of me with the square face and the dimpled chin. The Armenian immigrants I knew came from Lebanon, Syria and Iran. Here, to my surprise, was someone who spoke my own native language fluently and with the characteristic, slightly nasal tone of the educated class in Vienna, a city I had called home for more than 10 years.

Talkative and outgoing by nature, and often jumping between topics, Hovagimian told me his story over lunch a few days after the demonstration and in a couple of follow-up conversations: His grandfathers, Boghos and Sarkis, were among the 400,000 survivors of the Armenian Genocide. Boys of 8 and 10, they were living in Urfa, a city in the Southern area of the Ottoman Empire, when the deportation order arrived there on August 23, 1915. The Armenian residents of Urfa famously resisted the declaration to leave and defended their homes against the Turkish soldiers, but after five weeks, the Turks crushed the rebellion with the help of German led artillery. In all, 68 members of the Hovagimian family died in the uprising. Steven’s grandfathers fled across the border into Syria and found new homes in Al Quamishli, Steven Hovagimian’s birthplace.

Al Quamishli was a hodgepodge town, with Kurds, Armenians and Arabs coexisting peacefully. Living there until 1967, Hovagimian learned Armenian from his immediate family and Turkish from his grandparents, and on the streets he picked up Kurdish and Arabic. Later, he soaked up additional languages — French, German, English, Latin, Hebrew, Old Greek, Farsi, some Spanish — as though his life depended on it. “I strongly believe that each person is blessed with at least one gift,” he said. “I am bad in music and at fixing cars. But I love people, and I love to learn from them. Learning languages is easy for me.”

Steven was 4, when the Hovagimians left Al Quamishli for a new life in the Soviet Republic of Armenia where they wanted to join a movement that Stalin had initiated right after World War II: Offering free travel and financial start-up support, he encouraged Armenians all over the world to help ensure their culture’s survival by repatriating to what was left of their ancient homeland in the Soviet Union. Stalin harbored imperialist motives: if enough Armenians obliged, he would be able to justify a Soviet expansion into the formerly Armenian parts of Turkey.

Tens of thousands of Armenians from Europe, the Middle East and the Americas followed his call, but for Steven’s family it wasn’t meant to be. Planning to travel to Armenia via Lebanon and Georgia, they got stuck in Beirut when the Six-Day War between the Arabs and Israel in June 1967 put an end to the Armenian migrations out of Lebanon. The Hovagimians settled into a new existence in Beirut, and once Steven was allowed to ditch the girl-persona they became just another Armenian family that focused on faith, work and a good education for the children.

In April 1975, the Lebanese Civil War broke out. With boys as young as 12 being drafted into the conflict, Steven’s parents feared for both their sons’ lives. To keep them safe, they resorted to a measure so extreme that it can only be understand in the context of the Armenian trauma: They sent first Sarkis and then Steven off to live in the care of the Mechitarist monks, an Armenian Benedictine order, in Vienna.

For Steven, who was only 12 when he left home on July 26, 1975, the finality of the trip didn’t sink in right away. “I thought this would be a wochenendspaziergang,” Hovagimian told me, using the German expression for a walk in the park. For all he knew then, he was about to board an airplane for the first time in his life, about to go on an adventure to Europe, and soon he would see Sarkis. Steven was happy — though he also remembers feeling somewhat alarmed about his father’s behavior at the airport in Beirut: The man hugged him, and as they embraced, Steven saw tears in his father’s eyes. A man who dares to show emotion in front of his child? This was un-Armenian.

After a couple of days in Austria, Steven began to feel homesick. He asked Sarkis about returning home, but the brother said: You have two choices. You can go back to Lebanon, and you will die. Or you can stay here and be miserable, but then you will be somebody one day. Hovagimian never returned to Lebanon. While he didn’t see his parents for many years — the monks discouraged contact between their protégées and the families back home — he found ersatz parents in Vienna whom he calls Mutti and Vati (Mommy and Daddy.) “They came to visit on Sundays after mass,” he said. “We still skype.”

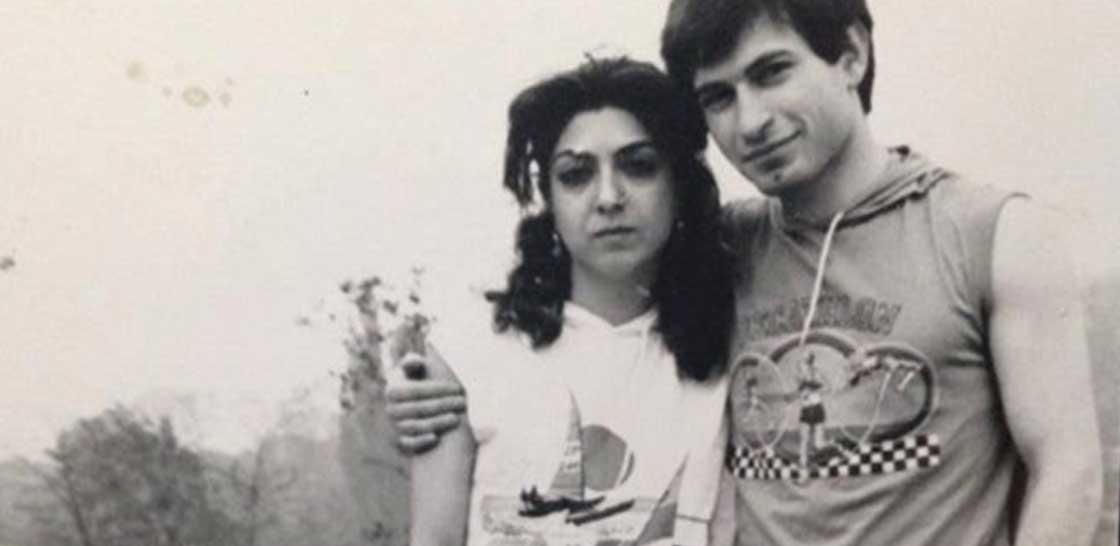

After graduating from high school, Hovagimian, like his brother before him, entered the seminary. Unlike Sarkis, he didn’t become a priest. As he was waiting for ordination the world caught up with him in the form of a woman, Julia, an Armenian émigré from the Iran of Ayatollah Khomeini. The two met through the United Nations refugee services in Vienna, where Steven volunteered as an interpreter on Julia’s case. They soon got married, and in 1984 they moved to the United States. “I wasn’t the monastic type,” Hovagimian said about his turnabout.

Over the years, Hovagimian has shown a remarkably high degree of adaptability while at the same time resisting full assimilation. It is a balance that his people have learned to strike, a survival mechanism: Armenians cling to their language and traditions, and they stick with their brand of Christianity, the Armenian Apostolic Church. Proud of their history, they continuously remind each other that their sacred mountain, Ararat, is the place where Noah purportedly found dry land after the deluge; that they were the first nation to adopt Christianity as a state religion; that they have a unique alphabet.

Against the fear of annihilation still haunting so many, stands a conviction that the writer William Saroyan expressed in words that Hovagimian’s daughter, Christine, knew to recite in Armenian at 5: “Destroy this race,” Saroyan said, “go ahead, destroy Armenia. See if you can do it. Send them into the desert without bread or water. Burn their homes and churches. Then see if they will not laugh, sing and pray again. For when two of them meet anywhere in the world, see if they will not create a New Armenia.”

The greater Los Angeles with about 350,000 Armenians is home to many such New Armenias. In Glendale 27 percent of the 190,000 inhabitants are Armenian; other hotspots, with about 5 percent Armenians, include Burbank, Montebello and Pasadena. Steven and Julia Hovagimian, who have two grown children, live in Tujunga. He is a social worker for the County of L.A., but his heart and his free time are with Armenian causes. He serves as a deacon in local Apostolic Armenian churches, hosts a local Armenian TV show and runs a small office in Glendale where he counsels Armenians on immigration issues. (“He likes to help people and sees the good in every person,” Julia says about her husband.) Most important to him, he supports the activities of the Unified Young Armenians, a Glendale based group that organizes Armenian language and history classes for the local community as well as the annual protest march in Little Armenia on April 24. “It feels good to work with the new generation,” Hovagimian said. “They are like sponges — and I will continue to live through them.”

Hovagimian’s parents died a few years ago. His siblings, Sarkis (aka Father Vahan) and Lucy, live in Vienna. Looking back, Hovagimian feels no resentment toward his parents for sending him away. On the contrary. “My parents are my heroes,” he said. “They were not so educated, but they attended the university of life. My mother told me: I had to go to bed every night crying that my two sons were not with me. But it made me happy that they are in a monastery with God, protected in a safe place. She cried. But she knew that we were in good hands.”

About the Author: Christina Schweighofer tells true stories. An immigrant from Austria, she is curious about cross-cultural experiences and their impact on new generations. Bilingual in English and German, Christina writes for U.S. as well as German and Austrian publications. She is a two-time L.A. Press Club Journalism Awards finalist and the founder and editor of Pasastainable, CA, an environmental news site about the sustainability movement in Pasadena, California. More information about Christina can be found at christinaschweighofer.com